Ironically, this is not an article on Israel exchanging land for peace. There have been countless articles written on its folly and there may be a lot to learn from the Israeli experience.

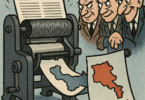

Negotiators and foreign policy pundits expect the Armenians of Nagorno-Karabakh to unilaterally cede land to Azerbaijan with an expectation of peace in return. The region of Nagorno-Karabakh (NK) lies between Armenia and Azerbaijan and is inhabited by Armenians. These Armenians fought Azerbaijan and won the battle to live on those lands as the Soviet Union was disintegrating. A Russian-brokered ceasefire was signed in 1994 and subsequently the conflict remained frozen. Less than a decade ago Armenian (representing NK) and Azerbaijani negotiators agreed, on paper, the principles of a peace agreement under which Armenia would relinquish buffer lands outside of NK proper in exchange for a deferred local referendum on the status of NK, ostensibly recognized by Azerbaijan, with some undefined form of international enforcement and peacekeeping force on the ground. This land for peace scenario includes the right of return of all previous residents. Clearly, this current proposal remains incomplete.

In the aftermath of July’s failed coup in Turkey, the rapid rapprochement between Turkey and Russia was partly predicated on expanding economic projects of joint interest, including the Turk Stream and Southern Stream gas pipelines carrying Russian gas to Europe, as well as unanticipated “common interests” in Syria. Reports of Turkey, Azerbaijan, and even Iran becoming associate members of Moscow-sponsored Eurasian Economic Union (EEU) requires an end to the NK conflict, for currently Armenia’s eastern and western borders are blockaded by Azerbaijan and Turkey. Since Armenia is a full member of the EEU, this blockade now becomes rather inconvenient. Even though the negotiation process between Armenia and Azerbaijan is spearheaded by the OSCE’s Minsk Group, whose members include the US, France and Russia, Russia has become the default regional power with varying strategic interests in both Armenia and Azerbaijan. Russia can single-handedly impose a solution to the NK conflict satisfying neither side. As an incentive, Russia could bring economic hardships to both sides while being the leading arms supplier to each. Note that Israel is Azerbaijan’s leading high-tech weapons provider and in return Azerbaijan supplies nearly half of Israel’s crude oil requirement.

Since the status quo in NK interferes with nascent Russian-Turkish-Iranian arrangements in the region, Russia is pressuring Armenia to accept some form of a land for peace scenario. It is not clear the level of Russian pressure exerted on Azerbaijan, but Azerbaijan’s hydrocarbon revenue and strategic relations with Turkey allow it to resist Russian pressure more than Armenia, regardless of Armenia’s so-called strategic relationship with Russia and membership in the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO). The status of NK was raised during recent meetings of regional powers Russia, Iran, and Turkey in Baku, and separately between Russian, Armenian and Azerbaijani leaders. Protests broke out in Armenia last month instigated by an armed takeover of a police station followed by popular support for the attackers. The armed group demanded no land for peace in NK, and the resignation of the Armenian government. The attackers eventually gave up amid aggressive police action. This popular unrest allowed Armenian leaders to point out the extent of popular dissatisfaction with a land-for-peace deal in NK.

Although simplistic, Israel having relinquished immediate control over Gaza certainly didn’t result in peace. Would returning the Golan Heights have made much of any difference in Syrian-Israeli relations? Perhaps we will never know now; besides, Israel appears to have annexed Golan. Without a multifaceted US guarantee as an external broker, it is not clear if peace with Egypt would have existed or prevailed after Israel relinquished control over the Sinai. The land-for-peace record is not very impressive.

The characterization of land for peace scenarios between Israel and the Palestinians seems valid in the NK case. When Azerbaijan had jurisdiction over NK there was no real peace between its Armenian inhabitants and Baku. The same situation existed in Nakhichevan, a Soviet-designated Azerbaijani-jurisdicted exclave on the western Armenian border, where its 50% Armenian population in the 1920s was reduced to nearly zero by the mid 1980s. If Russia remains the only guarantor of such an arrangement, it would have to guarantee the peace, as land would already be given to Azerbaijan – a fait accompli. This didn’t work during the Soviet period, has not worked since 1994, and there is no sign it can work now, especially given the level of corruption and extortion that can be waged by Baku. A change in government in Azerbaijan can also raise fears of any previous agreement being nullified. This was the fear when the Muslim Brotherhood took power in Egypt several years ago.

Wars of territorial gain eventually end at a negotiation table with the winner defined as the side that can enforce its gains. However, when one side simply gives up land for an equivocal concept of peace, one is subject to the vagaries of a requisite enforcing body. Imposed solutions are rarely permanent.