The following fictional Red Cell scenario is intended to stimulate alternative thinking and challenge conventional wisdom, tying together events in operational fiction with national realities.

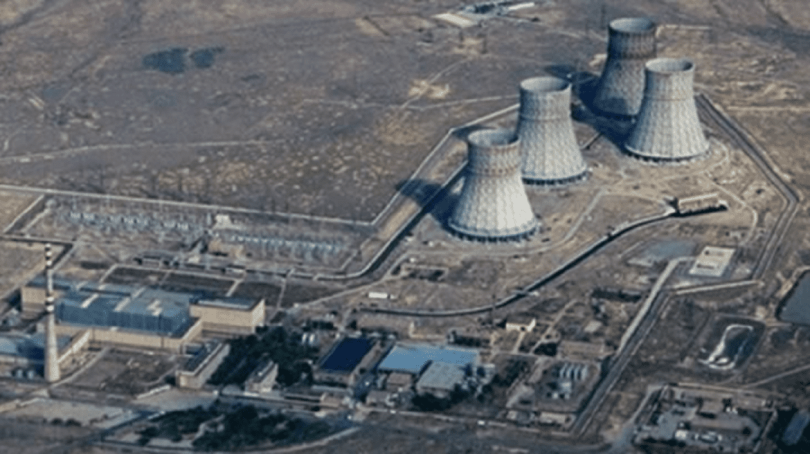

The spent nuclear fuel assemblies at Armenia’s Metsamor nuclear power station, near the border with Turkey, were indeed stolen and exchanged with dummy ones. The heist took place sometime after the entire nuclear facility was purchased by a diasporan conglomerate when it was closed by Rosatom, a Russian state corporation headquartered in Moscow. Even though technically the spent fuel was owned by that conglomerate, the disposition of the spent fuel is regulated by the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) and enforced by local governments. The seriousness of this incident forced the Armenian National Security Service (NSS), revamped from the early republic days into a near world-class institution, now fully able to learn from its mistakes, unlike its predecessor’s KGB-like philosophy that nearly resulted in Armenia becoming a failed state, to jump into action. This incident was by far the most momentous for the NSS. The consequences of this theft changed regional politics.

Where the spent nuclear fuel went was anyone’s guess. The leading hypothesis was that, secretly, this spent fuel made its way to Israel as part of a technology agreement that had been in place for over a decade, signed in 2001. Armenian media quieted the rumors in concert with Yerevan’s crack diplomatic corps and Armenia’s eager-to-serve diaspora. Was it possible that Armenians attempted to reprocess and extract plutonium available in this fuel to build a nuclear weapon? Even if only one percent or so of spent fuel was plutonium, more than enough for a weapon, nuclear reprocessing is nasty technology requiring the hundreds of fuel assemblies stolen to be chemically and otherwise treated to extract plutonium and any remaining uranium-235. Plutonium was the prize due to its physical properties in nuclear weapon design. Ironically as for a bomb design, when the United States publicly posted the millions of Saddam Hussein’s government documents, hoping they would add additional justification for the destruction of Hussein’s Iraq, it included Iraq’s atomic bomb design. This bureaucratic oversight was immediately corrected, but not before the plans were downloaded.

Armenia’s nuclear and chemical experts repatriated to Armenia after the collapse of the Soviet Union had a considerable advantage over Israel’s nuclear program. Israel needed the “research” reactor at Dimona to quickly create plutonium-rich spent fuel. Dimona used heavy water moderation, breeding plutonium. In contrast, Armenia’s Metsamor plant had a massive store of “regular” spent fuel.

After Armenia completed the revamping of its NSS, much to the chagrin of its immediate post-Soviet ruling oligarchy, sometime after 2001, a covert division was created. The division’s charter was to propose policies on the integration of advancing technologies in Armenia but, more importantly, to investigate high technology crimes. Such crimes were outside of ordinary police capabilities. The name of the NSS division has never been published but is otherwise known as “The Division.”

Armenian internal, external, intelligence and security bodies operate under one umbrella and are highly compartmentalized. Sometimes this resulted in duplicated effort and seeking competitive recognition. Was the disappearance of this spent fuel part of a very top-secret operation under the protection of another organization within the NSS, the government itself, or some operation run by outside powers? The Division hired extra scientists and nuclear experts considering if Metsamor’s entire spent fuel pool were emptied, the result would be:

1 – It was sold.

2 – It was destined for reprocessing, ending up in a nuclear weapon.

3 – There was enough highly radioactive material to make hundreds of dirty bombs.

Meanwhile, Armenia’s NSS was receiving scores of urgent requests for the status of this spent fuel pool from nuclear security and intelligence organizations worldwide. The NSS was constantly updating these intelligence organizations on The Division’s progress. The United States Defense Intelligence Agency (US DIA) put enormous pressure on Armenia. Western mainstream media was accusing the Armenian government of nefarious activities coming ever closer to threatening an investigative invasion of Armenia in violation of its sovereignty. The United States demanded that its investigative advisors be included in the effort being expended by The Division. Armenian diplomats in the US supported this move but strongly suggested Armenian-speaking experts be included.

The Division was in a massive search, identifying any footprints of the process known as plutonium uranium reduction extraction, or PUREX, as it is known in the reprocessing industry. The Division was looking for any storage facilities or even a series of small firms supplying nitric acid. Nitric acid dissolves spent fuel as part of its eventual chemical separation. Such reprocessing is a complex chemical, electrical, and mechanical process, requiring a lot of electrical power. Armenian Aerospace’s military satellites were being used to detect any abnormal radiation, or worse, radiation plumes, but to no avail. Still, undoubted, any fuel rods would be extracted underwater. Spent fuel is stored underwater to absorb and shield radiation. In addition, water extracts heat still generated by newer fuel assemblies recently moved out of the reactor. The Division knew that to have pulled off this heist required incredible secrecy and technical expertise.

Investigators studied the backgrounds of those who worked for the Mergelyan Institute, the Yerevan Physics Institute, and scientists who worked at various research institutes across Armenia during the Soviet period. Nobody appeared out of place, except it was noted that a group of semi-retired Armenian chemists and chemical engineers from Baku seemed to be using advanced encryption on their cell phones and email traffic. The Division knew of Armenian-Israeli collaboration on advanced encryption, but its status was unknown considering the joint effort was barely six months old. In any case, the chemists were detained for questioning. The interrogations were intrusive, with each person separated and offered limited immunity if they told investigators what they knew – ratting out one another. Among the detainees were several Israeli nuclear chemists. The Division thought for sure they were on the right track. Still, the depositions given by almost all the detainees were strikingly similar but not enough to determine why they were identical, nor enough to arrest them. They were under heavy surveillance.

The end use of the spent fuel: transfer to another country, reprocessing destined for a weapon, or used in dirty bombs, required coordinated parallel efforts in this high-technology search. The Division was dumbfounded; how could hundreds of fuel rods, shielded underwater in seven-meter length assemblies, each weighing four to five hundred kilograms, be transported without detection? Further, transportation required water shielding in metal containers of some kind.

A bit odd, but The Division discovered that a little-known mining company used nitric acid to dissolve limestone in an undisclosed location in the Armavir Province of Armenia. Limestone is associated with extracting lithium (used in rechargeable batteries), recently discovered in various places in Armenia. It appeared the Chinese funded a joint venture between Armenian and diaspora chemists to mine lithium in Armenia. Thousands of liters of concentrated nitric acid were imported into Armenia to create tunnels, obsessively facilitating easier limestone extraction. The result looked like caves. Records show this limestone was transported to lithium refineries in Armavir province using old Soviet-era cement trucks, with their mixers modified. The cement barrel was replaced with a stainless steel container typically used to transport nitric acid but interestingly painted the same dull white color as the original Soviet-era trucks. Local Armenian chemists, under investigation, purchased these trucks from a wholesaler in Krasnodar, Russia, near Crimea.

The Division knew of a large shipment of nitric acid that arrived in Armenia several months earlier from Iran. The paperwork all pointed to the lithium mining firm. Investigators and military security teams rushed to the limestone caves. They found nothing but a hundred or so shafts that looked like caves from a distance, each about three meters in diameter. Most of the shafts showed evidence of deep cylindrical impressions on their floors. The last heavy truck tracks were all leading out from the caves. Investigators hypothesized that the spent fuel might have been placed in cylinders stored in these caves but subsequently removed. Tire tracks leading away ended at the main highway. This was one of the new highways extending to a Turkish border station. Immediately, Armenian investigators rushed to the border station inquiring if any heavy trucks were recorded crossing the border or if any other vehicles were stopped due to traces of nuclear contamination. Several trucks were recorded as passing Turkish customs, but they were empty. The Armenian inquiry started a frenzied investigation, but Turkish authorities were stretched very thin due to internal civil strife. The Division hypothesized that the chemists’ activities were diversionary because there were no official records of lithium deposits in Armenia. However, from what were the chemists diverting attention?

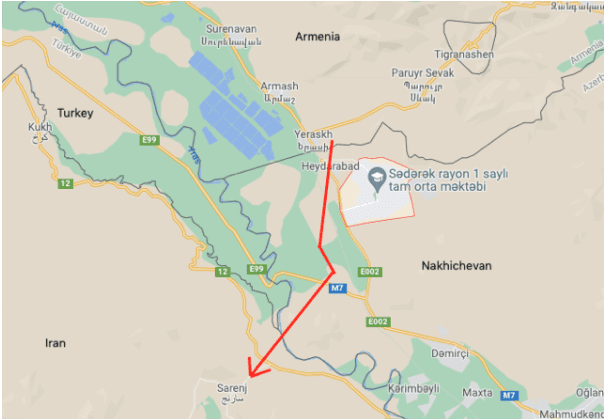

The plan was to transport all the spent fuel through the Azerbaijani exclave of Nakhichevan into Iran and Iraqi Kurdistan. Once strong during the Soviet era, Nakhichevan’s border with Iran was relatively porous. This transfer was the most complex and dangerous part of the operation, the most daring and ambitious effort ever attempted in the region. Transport timing and logistics needed to be addressed, and so did the Iranians. It was agreed that more than half the spent fuel would be given to Iran. The Iranians would receive all of the recently irradiated fuel rods removed from the Metsamor reactor during the past decade. The Iranians would have enough plutonium for many compression-type nuclear weapons or even neutron bombs after this spent fuel was reprocessed.

Fuel assemblies recently removed from the reactor are the most dangerous spent nuclear fuel, glowing blue underwater and still physically hot from ongoing nuclear decay. If any part of this last leg of the spent fuel journey, through Nakhichevan, were known, it would be detected and intercepted in a matter of minutes. Each spent fuel assembly in their stainless steel containers filled with water was transported from the Armenian town of Yerask through about ten km of Azerbaijani territory crossing the spotty-patrolled Iranian frontier close to Sarenj, Iran. Driving trucks through this semi-deserted land was out of the question, even if the diesel cement truck motors were silenced. The decision was to use seventy-meter long dirigibles, or airships designed by the Iranian Space Research Center, minus the propellers and drive motors. There was some discussion about installing electric motors, but the battery weight, motor, propeller noise, and unneeded additional complexity would add more points of failure to an already near-impossible mission. Tests were run in Iran with small SUVs towing the airships several hundred feet above the ground. Towing was also tested using horses, mules, and people. The process really took a high level of coordinated talent since controlling each dirigible required a minimum of three sets of nylon ropes, two in the front and the third tied to its rear.

The dirigibles needed to be hovering low, not visible to radar, colored with dark camouflage with radar-absorbing paint. The total length of this transport nightmare was about fourteen km, requiring a dirigible speed of at least 2.5 km/hour, and all this while avoiding forested areas. The operation had a crack team of scouts up to several km in front of the airship convoy. The M7 highway leading into/out from Turkey into Nakhichevan’s E002 road was barren, given the enveloping civil crisis in Turkey. However, contingencies were planned to stop any traffic if the dirigibles would be seen crossing the M7. In addition, a diversionary plan was put together with a border incident at the far eastern side of the Azerbaijani-Iranian border at Astara. The incident would be minor but artificially dragged on for two nights by Iranian authorities, giving enough time to move the spent fuel into Iran. Three loaded dirigibles crashed in Nakhichevan, requiring their immediate burial. It took nearly twenty men per burial site several hours to dig graves for the balloon material on the first night. An unloaded, spare dirigible for every ten loaded with spent fuel cylinders was necessary. However, on the second night, a single cylinder was left in an open area to demonstrate Azerbaijani culpability.

Additional diversions took place in Armenia, requiring much of The Division’s investigative time and energy. The first was an internet leak of the activities of the chemists using advanced cryptography. While the chance of clandestine spent fuel reprocessing being undetected is nearly zero, still, The Division had to hire world-class cryptographers to decode what was in the chemists’ communications and then track down their activities which looked like a research project using nitric acid and helium (destined for the dirigibles). The chemists created quite a mystery for The Division. In an additional diversion, the chemists placed two previously crashed drones with a load of radioactive material that could have come from spent fuel reprocessing. These were made to look like dirty drones — transport mechanisms to spread deadly nuclear contamination like dirty bombs. The electronics appeared to be shielded against gamma radiation from the spent fuel, supporting the impression these were indeed dirty drones. Both were found in the northeast of Armenia near the Georgian border, one in an old car, purposely contaminated with radioactive material, and the other a few kilometers to the west in a field near a well-traveled road. The Division spent weeks tracking the origins of the “dirty drones” complicated by the old car being an old Soviet-built Zhiguli with Azerbaijani license plates.

Were there multiple operations taking place with Metsamor’s spent fuel? The plan was to supply fissile material to an Iraqi Kurdish nuclear weapons program with covert help from Israel and France. It was an Israeli political calculation to change the regional dynamics with Iraqi Kurdistan instantly becoming a nuclear power, a state challenging both Iran and Turkey. Israel knew as soon as Iran found out about the Kurdish bomb, it would put its nuclear weapons program at high speed, shining international spotlights on Tehran. Dire warnings were issued from world capitals against Iran’s overt bomb program. Western mainstream media tied Armenia’s spent fuel theft to Iran. Since Armenia’s short border with Iran was secured by international security forces, Azerbaijan was later implicated in enabling transport of this spent nuclear fuel, especially since somebody leaked photographs of the dirigibles and the purposely deserted spent fuel container on the ground in Nakhichevan.

Iraqi Kurdistan, now just Kurdistan, saw the covert buildup of massive US and other western investment and intelligence operatives during the previous two decades. In reality, Kurdistan didn’t have an operational nuclear weapon yet, but it could in less than a year. The Kurds had Saddam Hussein’s AQ Khan’s bomb architecture. Perception is reality, considering Israel was prepared to supply Kurdistan with a low-yield nuclear device to be used for demonstration purposes, not unlike what Israel prepared for in the 1973 Yom Kippur War. Turkey massed its forces on its Iraqi border with nearly half a million soldiers.

After the Second Crimean War in 2023, Turkey was nearly bankrupt when Russians fought against Turkish-sponsored Tatars and imported ISIS fighters. Russia also blockaded Georgia’s Black Sea ports and closed its frontier with Georgia. Georgia was in a terrible economic condition since Turkey was Georgia’s leading trading partner. With Turkey nearly a failed state, its Islamic government began instituting strict Sharia law as internal social and economic decay was hurling Turkey towards complete collapse. Turkey was forced to sell off much of its military technology to Azerbaijan and Pakistan. NATO was forced to amend its articles of alliance with Turkey reduced to having NATO observer status. The US removed all its B61 hydrogen bombs months earlier as Turkish ultranationalists attempted to gain access to this nuclear arsenal for the third time. It wasn’t clear what these Grey Wolves would do with such weapons during the civil war between Islamists and nationalist Turks.

Former Iraqi Kurdistan, now The Republic of Kurdistan, demanded self-government for Syrian Kurdish regions. This demand was trivial since Turkish forces had withdrawn entirely from Syria. Syria’s Assad reluctantly agreed, considering a combined Syrian Kurdish-Arab force captured Turkey’s Hatay Province. This previous Syrian province was in Syrian hands with its tourist infrastructure intact. Assad quietly stepped down from power, and a French-led force was invited into Syria as part of a vast infrastructure reconstruction. As part of the negotiation on Turkey’s NATO demotion, Turkish Cypriots who preferred to live under a Turkish regime were transported to mainland Turkey as Cypriot forces restored Turkish-occupied northern regions to Nicosian jurisdiction since Turkish soldiers had long since withdrawn.

Even though Iran was forced to change its political persuasion, Turkey became a failed state with Kurds in northern Syria joining forces with their brethren in Turkey; the Division itself had a bigger problem. The IAEA secretly informed The Division that twenty-four Metsamor fuel assemblies were unaccounted for. The US DIA was harassing Armenia for an explanation. The Division always knew that the large numbers and expertise of the chemists’ group made little sense for just a diversionary effort.

The US DIA accused Armenians of having received a functional atomic bomb architecture from Iraqi Kurds – not based on Saddam Hussein’s purchase from AQ Khan. These plans were given to which Armenians? After The Division deciphered some of the chemists’ encrypted communications, it was discovered that Iraqi Kurds were working with Armenian nuclear experts all along. Unknown to outside investigators, The Division could not determine what was going on with any Armenian weapons plans. The Division reached an investigative wall, massive political pressure and threat of international sanctions were building on Armenia again.

Several weeks later, NSS and The Division directors were invited to a private meeting in an underground location somewhere in Armenia’s Armavir Province. The directors met with people they had never heard of previously but were told they represent those who implement Armenia’s Grand National Strategy. The directors were told a story beyond all expectations. Ten years earlier, twenty-four of the oldest spent fuel assemblies were removed from Metsamor’s spent fuel pool, replaced with dummy assemblies, unbeknownst to Rosatom. Armenian nuclear chemists adopted a pyro-chemical reprocessing method, previously in the experimental stage but made it operational underground in Armenia.

Armenians had slowly reprocessed enough plutonium for several atomic bombs. Further, Armenians secretly licensed this process to both the Japanese and South Koreans. It was never publicly disclosed if Armenia had assembled nuclear weapons and a means for their delivery. Instead, the NSS and The Division were told, “Armenia does not admit or deny having nuclear weapons, and that it will not be the first to introduce nuclear weapons in the region.”

Author: David Davidian (Lecturer at the American University of Armenia. He has spent over a decade in technical intelligence analysis at major high technology firms. He resides in Yerevan, Armenia).