David Davidian*, Yerevan, Armenia November 2018

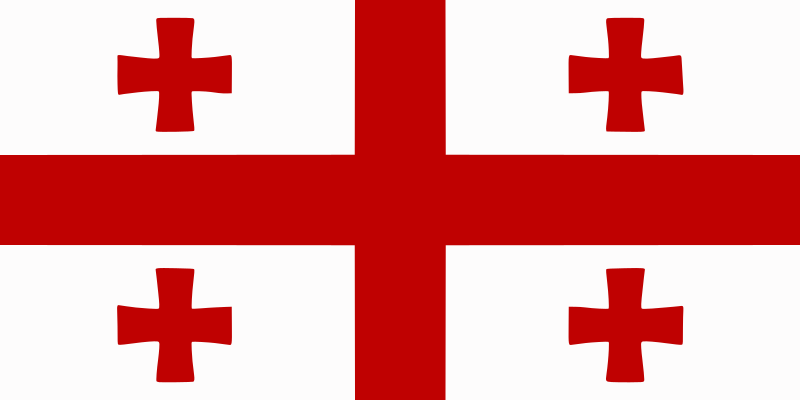

Abstract: The Republic of Georgia is among a class of small states under strong economic, political, or strategic influence that steers their foreign affairs to such an extent that policy deference is exhibited regarding any recognition of the Armenian genocide. Full recognition associated with land reparations, or tacit recognition of the Turkish genocide of the Armenians, has not been entertained by any Georgian government, regardless of the historical friendship exhibited between Armenia and Georgia. Land reparations from the Republic of Turkey to Armenia, such as those proposed on the accompanying map, would eliminate the current Georgian-Turkish frontier.

For these reasons no spontaneous genocide recognition policy has been expressed from the Republic of Georgia. However, long-term Georgian policymakers should consider the prospect of full genocide recognition that includes land reparations offered Armenia, replacing Georgia’s southwestern frontier. Georgia currently enjoys revenue-generating hydrocarbon transportation pipelines on its territory, yet can participate in the creation and expansion of new Armenian Black Sea ports and unidirectional transportation corridors. Georgia’s new southwestern frontier with Armenia can buffer, moderate, or eliminate expansionist regional powers, creating the basis for a new dynamic in the southern Caucasus.

Current Georgian Policy: The Republic of Georgia does not recognize the genocide of the Armenians as official state policy. The February 2015 limited political impact visit of the Chairman of the Georgian Parliament to the Armenian Genocide Memorial in Armenia represented the height of Georgian government concern regarding this genocide. For Georgia, the cost of non-recognition is easily outweighed by the explicit policy of denial by two of its strategic partners, the Republics of Turkey and Azerbaijan. The level of economic investment and integrated regional projects Georgia has with both Turkey and Azerbaijan is considerable, and as a result, Georgia is somewhat helpless on several international fronts, one being Armenian genocide recognition.

Background: After Russian forces evacuated the eastern Armenian plateau and the southern Caucasus in 1917, during WWI, many Armenian genocide survivors took refuge in the former Georgian province of Tsarist Russia. The descendants of these refugees today trace their lineage to the Kars and Erzurum regions. Bolshevik Russia, with the 1921 Treaty of Kars which demarcated the Turkish-Soviet borders, ceded former Georgian and heavily Armenian populated lands to Turkey. Both Turkey and Azerbaijan have abrogated specific tenets of this treaty since the disintegration of the Soviet Union.

From 1945 to1953 Moscow proposed several initiatives for annexing to the Soviet Union former Armenian and Georgian-populated regions of northeast Turkey centered on the provinces of Kars and Ardahan. Some proposals included territory from the Black Sea to the southwest of Lake Van. These post-WWII war reparations and related initiatives were supported by both Soviet Armenian and Soviet Georgian leaders. However, such proposals were opposed by the United States and Great Britain in many international forums and were eventually abandoned.

However, with Georgian EU integration may come pressure for Tbilisi to join much of the EU in recognition of the Armenian genocide. Many EU member states, the European Parliament and an increasing number of countries recognize the Armenian genocide.

A land transfer, as part of Turkish genocide reparations, will result in sovereign Armenian access to the Black Sea, expanding and vastly diversifying Armenia’s arable land, mineral resources, etc., where:

- Georgia will have a new significant partner in the regional mix with direct access to north-south trade routes, increasing competition, adding strategic new partners and enhancing trade negotiations.

- Georgia’s current energy transport systems will continue unhindered across its new southwestern border.

- A self-sufficient Armenia consequently reduces the coercive influence of regional powers in advancing their agenda on Armenia and adjacent territories, allowing relations to take place between Georgia and Armenia based on their mutual interests.

- Newly created supply routes into Armenia would significantly reduce the political pressure put on Georgia as Armenian’s main supply route.

- Ethnic and religious influences on specific Georgian minorities will be significantly reduced with pressure removed from Georgia’s southwestern border allowing minority cultural integration into the larger Georgian society.

- A self-sufficient Armenia can participate in east-west and north-south energy transport as well as providing enhanced routes for New Silk Road initiatives.

- Georgia can re-establish custodianship of its historical monuments and cultural icons on this land reparation.

In summary: Georgia’s position on any or full recognition of the Armenian genocide is greatly influenced by its two strategic partners; Turkey and Azerbaijan. It would be politically prudent for Georgian policymakers to take into account the possibility of full Armenian genocide recognition with its associated geopolitical ramifications. With Turkish recognition and land reparations, the entire political dynamic of the Southern Caucasus will change, replaced with widespread political and economic cooperation and healthy competition.

* David Davidian is a US-born citizen residing in Armenia. He is an Adjunct Lecturer at the American University of Armenia.