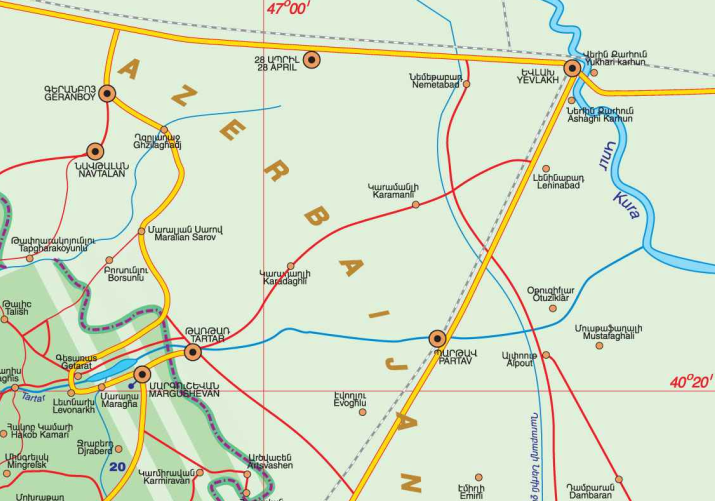

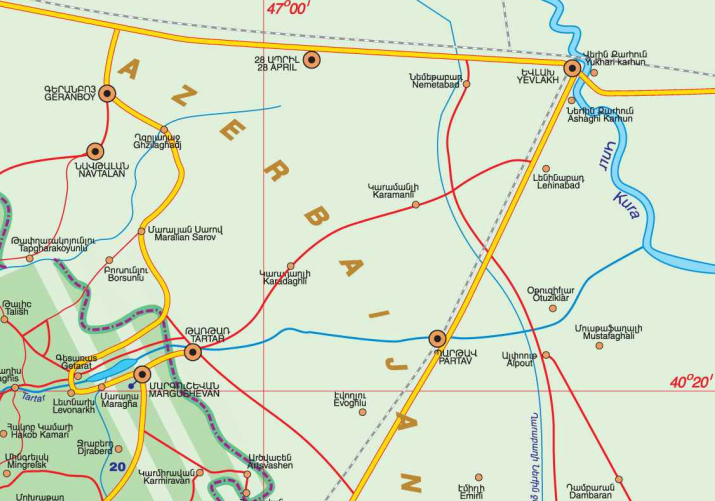

One need only look at a map of Azerbaijan and Nagorno-Karabakh to see how close the recent fighting is to the Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan (BTC) oil and the Baku-Tbilisi-Erzurum (BTE, also known as the South Caucasus Pipeline) pipelines. A downhill stretch of about 40 km separates the current frontline from these pipelines, making them extremely vulnerable to attack. Numerous articles in the Armenian press and social media report that Azerbaijan is emptying villages of its residents along a track from the towns past the farthest northeast border of Nagorno-Karabakh towards Yevlakh (see top and upper right on the map).

These pipelines are capable of transporting over a million barrels per day of oil and almost 9 billion cubic meters of gas per year from Azerbaijan’s Caspian hydrocarbon fields. They start at Baku and are laid across Azerbaijan from southeasterly to its northwest. After passing the Georgian border, the BTC pipeline passes near the Georgian capital, Tbilisi, continuing on to the Turkish Mediterranean coast. The BTE line goes to Erzurum, Turkey. A third, an updated Soviet-era pipeline, known as the Baku-Supsa pipeline, parallels these other two in Azerbaijan, diverging and passing north of Tbilisi and terminating at the Georgian Black Sea port at Supsa. Under construction is the Trans-Anatolian Natural Gas Pipeline (expected operation in 2018). BP and its partners alone invested more than $50 billion in Azerbaijani energy projects and infrastructure.

Map showing the short distance between Nagorno-Karabakh (dark green), the front (stripped green) and to its northwest Yevlakh. The BTC pipeline generally follows the railroad (dashed) and road (yellow).

Rumors continue to circulate in Armenia that these pipelines can and will be seriously damaged if the conflict intensifies beyond early April’s Four-Day war between Azerbaijan and Nagorno-Karabakh. While the cut-off of these hydrocarbon highways would not seriously impact world energy supplies, they would affect the coffers of the State Oil Company of Azerbaijan (SOCAR), reduce the gas supply to Georgia by at least 90%, and to a lesser degree (10%) Turkey. However, half of Israel’s crude is purchased from Azerbaijan, forcing it to secure spot contracts to make-up for the loss if Azerbaijani pipelines were destroyed.

The vast majority of Azerbaijan’s economy is hydrocarbon based and a leading characteristic of such economies is the low priority given to diversification, especially in the post-Soviet space. Even though Azerbaijan has already passed peak oil and today’s crude is less than one third its high market value of nearly $150/bbl, Azerbaijan’s leadership and oligarchs understand the impact of losing revenue that cannot be replaced if this pipeline infrastructure is severely damaged. This is perhaps one reason why Azerbaijani officials have stated they would rather engage in a battle of attrition against Armenia and Nagorno-Karabakh than an all-out attack. This fact was noted during a December 5, 2014 conference at the Carnegie Center in Moscow by Senior Associate Thomas De Waal.

However, political and economic conditions have changed since the end of 2014 and the chance of serious damage to these pipelines has been raised. The average wage in Azerbaijan has just dropped below that of Armenia because Azerbaijan’s economic infrastructure is mainly indexed-off of hydrocarbons. Budgets have been lowered, and projects slowed or abandoned. Baku has issues paying Moscow for its heavy weaponry, noted in the Russian press. A policy that was once predicated on not seriously breaching the 1994 cease-fire between Nagorno-Karabakh and Azerbaijan, keeping the pipelines full above all else, appears to have been compromised. The latest fighting, known as the “4-Day War” was not a miscalculation or an accident waiting to happen, but rather a planned offensive across the eastern front streaking from close proximity to these pipelines in the north to nearly the Iranian border to the south. Initially, Azerbaijan captured tiny swatches of land in no-man’s land, several hundred square meters here and there, supported by hi technology weaponry. The result: basically a military draw that took the lives of many hundreds and wounded perhaps thousands.

A negotiated settlement between the warring parties, taking into account realities on the ground, will allow the residents of Nagorno-Karabakh to live in peace and create regional stability ensuring unfettered transport of energy reserves to waiting markets.

*David Davidian is an Adjunct Lecturer at the American University of Armenia. He has spent over a decade in technical intelligence analysis at major high technology firms.