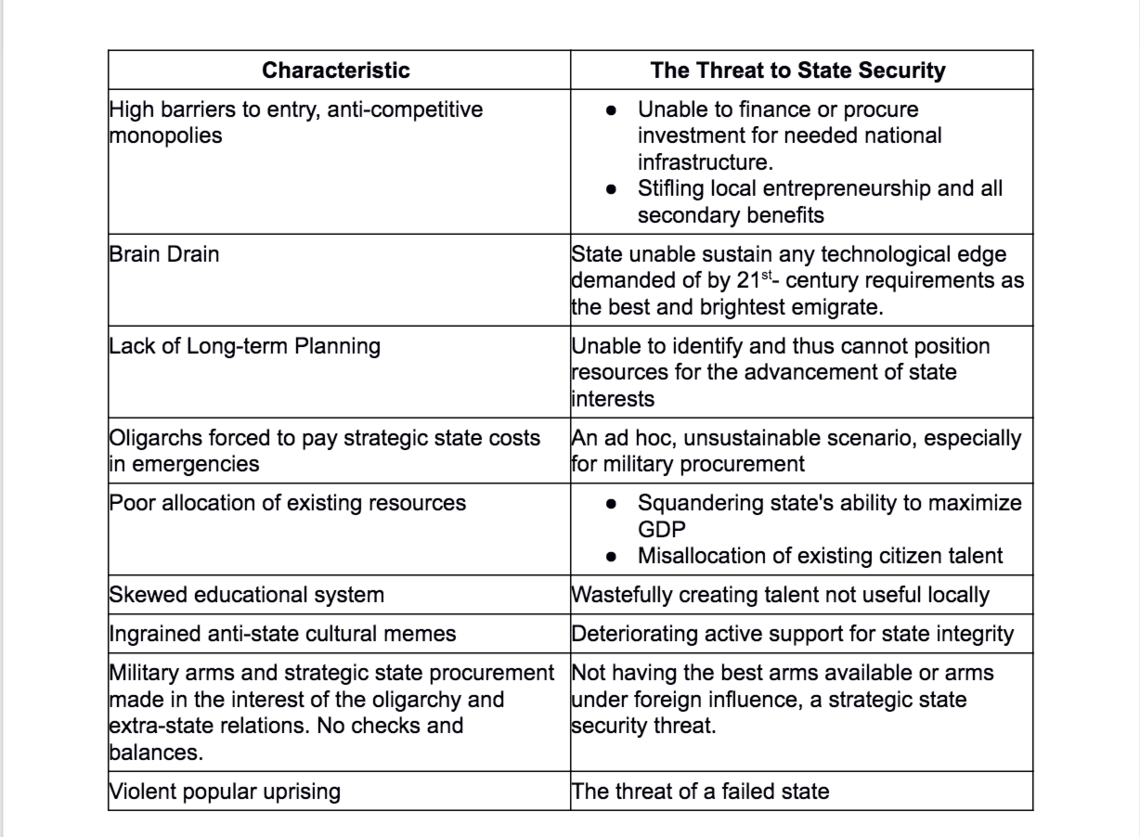

Characteristics of Small-State Oligarchies

Low external investment with high local barriers to entry

The success of any investment is predicated on conditions associated with risk and return. No institution will ever invest in a state where the legal system is biased in favor of local oligarchs, to the direct detriment of the institution. However, it must be pointed out that it is not uncommon for “established international institutions” to make deals with select local structures, groups or institutions, serving larger political goals fronted by those institutions.

Small states often engage in the procurement of international loans. Lenders look at factors such as the projected increase in GDP and overall economic diversity in establishing the return on given risk. Overestimates of these factors used to attract investments can result in a considerable burden on the state and its people when economic development metrics have been manipulated. If the state treasury or tax revenue cannot fund repayment, the tax burden is increased on the population, an undesirable condition with possible popular repercussions. In some extreme cases, oligarchs themselves are asked to provide strategic funding shortfall.[3] While direct proof is difficult to ascertain, the chances of small states having to turn to oligarchs to fund the procurement of arms is likely.

Brain Drain

A classic brain drain occurs when highly skilled citizens leave their native country, generally seeing employment in another when there is a critical disparity in economic conditions between the source and sink states. A brain drain can also result when skills are no longer locally necessary due to once-in-a-lifetime socio-political events or economic structural change. Both took place on a vast scale during and after the disintegration of the Warsaw Pact states and the Soviet Union. Hundreds of thousands of skilled individuals whose expertise was primarily utilized in the Soviet military found themselves subsequently unemployable. Many of these talented citizens left their native lands and others for varying reasons remaining underemployed. An excellent example of using brain drain talent took place in Israel where many thousands of the best and brightest left during and after the disintegration of the Soviet Union and now serve the strategic interests of the state of Israel.

Other factors that contribute to a brain drain include racial or ethnic discrimination, lack of societal meritocracy, the arbitrary rule of law, threats of terrorism, chronic civil disorder, etc. In oligarchies, due to the immediate goal of accumulating wealth, power and influence, there is an under-appreciation of the market loss due to a continual brain drain. In some oligarchies, a brain drain is welcomed as it deters and diminishes competition. This comes at a loss for the overall society, small-state security and ultimately the oligarchy itself.

When local institutions of higher education graduate highly capable individuals and when such skills are not allowed to be used for the benefit of both the individual and society, the result is an irreplaceable loss for the state. When it is much easier for a new graduate to secure employment by emigrating rather than contributing to the betterment of their native society the government has failed in its purported contract with its people. The result is local institutions of higher education fuel a brain drain rather than growing the local economy. Further, meme and innuendo about the inability to succeed in an oligarchy become the end in themselves, where the default overtones are that the road to success is emigration. While this might not be of immediate interest to the monopolistic oligarch, it will eventually, as the small state is unable to maintain itself in a dynamic world consisting of states that do engage in active competition and long-term planning. As the political intensity of the small-state oligarchy increases, their captive markets proportionately decrease in size.

Brain drains are usually associated with the educated young and vibrant citizens, leaving behind an aging population, forcing additional burdens on the state structures. Usually, capable individual family members emigrate and in return provide remittances to family and extended family members. Depending on political conditions, such international monetary transfers might be a source of blackmail.[5]

Misallocation of Existing Talent

Chronic misallocation of talent within a society creates a culture of skewed skills, a misaligned educational system, and stifles entrepreneurship. This squandering of talent takes place when intelligent, skilled, and talented members of society are forced to engage in activities well below their potential, forced to remain underemployed, or work multiple insignificant part-time jobs. While no government should guarantee full employment, an oligarchy will force otherwise first-rate talent to the periphery as bureaucratic and mafia-like tactics are used to stifle a meritocratic competitive environment. Keeping a population near the base of Maslow’s hierarchy is characteristic of medieval kings, and certainly is not part of an internationally competitive 21st-century state.

A consequence of this misallocation is a direct threat to state security. Let’s take a small state that may have been defeated in a border conflict or a cyber-attack having disabled a mobile telecommunications infrastructure. In the former situation, state defense coffers may have depleted, pilfered, or weaponry may have been procured without the necessary military considerations taken into account. Corruption associated with arms sales has been exhibited throughout modern history.[6] When adequate local talent no longer exists to support even basic weapon research, development, and manufacture, it forces the state to rely on externally produced strategic arms. Under static and non-threatened security conditions, it may appear less arduous to purchase weapons than to gather and manage research, development, manufacture locally. Such careless disregard of local talent would inevitably reduce strategic state security as the small state becomes even more dependent upon larger regional arms manufacturers. In the case of a cyber-attack, both defensive preventative and retaliatory measures cannot be afterthoughts but must have been part of an ongoing national cyber defense initiative, especially in this era of hybrid warfare. Without security-vetted local talent filling the demand for such state-of-the-art high tech positions, coordinated by leadership with accumulated knowledge and expertise, all resulting ad hoc efforts would fail.

States with the majority of their GDP driven by hydrocarbon exports are characterized by a critical lack of overall industrial talent. Most oil and gas producing states are riddled with corruption, and the resulting lack of necessary local skills directly contributes to the state’s inability to diversify their economies. Even worse, in many cases the established oil and gas extraction and transportation expertise are foreign. Although these states claim they want to diversify, diversification is at best on paper only. Even if oligarchs in hydrocarbon-based economies understand the necessity for diversification, little or no diversification can take place. Oligarchic policies engender poor human capacity building. The Brookings Institute[7] has concluded that only 2 of the 17 oil generating countries meet their test of significant diversification.

Lack of Long-term Strategic Planing

Many oligarchs and leaders of oligarchic states are themselves “diversified” having laundered their questionably-obtained holdings in the form of real estate, investments through international shell corporations, etc. There is abundant literature about such mechanisms. While a considerate effort is put into the survival of private portfolios, long-term planning is predicated on simply “jumping ship” as witnessed in many post-Soviet states.

Incomplete National Defense

Rarely, if ever, does a small state take unilateral actions against the interest of strategic powers, thus defining the anarchic international relations schoolyard. However, this does not preclude a small state from maximizing its ability to defend itself from external aggression using all its available capabilities. The latter cannot be fully accomplished without the most capable citizens being allowed to produce goods, services, technologies and equally as significant, resulting secondary and ancillary indigenous sectors addressing the myriad of 21st-century technological demands. Merely having sufficient talent serving an oligarchy is no substitute for the best.

Regional powers take advantage of weak, unrealistic, or non-existent long-term small-state planning. As a result, the small state may slowly become subservient to the benefit of a more powerful regional power. The security dimensions are apparent even if small-state interests dictate vectoring away from being a dependent entity. This servile condition may not appear to be a concern since long-term strategic planning is usually not part of the small-state oligarchic lexicon.

Not only has the small-state oligarchy severely suppressed the indigenous capability of developing and producing a minimum acceptable level of defensive military armament, but with policy-limiting GDP and selective monopolies covertly exempt from tax collection, the state becomes trapped by the quantity and quality of procured foreign military arms. This dynamic is a vicious circle as regressive economic strangling directly compromises a small state’s ability to defend itself, on its terms. Even larger state defense establishments are riddled with corruption and graft, limiting their ability to wage an optimized military defense.[9] Examples include: Afghanistan, Pakistan, China, Columbia, Ukraine and many more. Small countries are generally at a disadvantage relative to the amount of defense funding available, usually measured in percentage of GDP. Since long-term planning is a challenge to an oligarchy, military capabilities would remain at the tactical or sub-tactical level, unable to conduct a necessary national defense given the emerging demands of 21st-century threats.

It is possible that the defense policies of the state coincide with those of the oligarchs. However, the line between legitimate state defense and a threatened oligarchy is usually a function of the number of soldiers on the streets.

Popular Demand for Expelling Oligarchs

Perhaps counter-intuitive, but, the immediate disappearance of an oligarchy is not in the interest of the civilian population. The impending disruption of transportation, maintenance of vital infrastructures such as banking, water, electrical grid, garbage collection, policing, food staples, etc., and most importantly the military would push the state towards failure. If the state were under an immediate military threat, this disruption might result in catastrophic consequences. Further, the reestablishment of markets and distribution channels would place an incredible burden on its citizens and interim or follow-on governments. Some of this was seen with the disintegration of the Soviet Union. Popular protest against an oligarchy or governmental systems favoring oligarchs is generally never accompanied by a well thought out replacement plan. The fulfillment of the demand that oligarchs disappear overnight from within political ranks is not only an illusion but is in nobody’s interest.

The Oligarch’s Dilemma

The difference between the functioning of an oligarchy and its businesses is in stark contrast with established firms which have survived equal-footed competitive environments. Oligarchs understand their position is temporary and they run somewhat scared as their actions are recognized as unpopular. Oligarchs usually have personal bodyguards with armed guards at their residences and business. Such is rarely the case with the leadership of firms having survived well over a century in a competitive environment. Some of the latter include firms such as Mercedes-Benz, IBM, and Škoda Auto. Japanese firms that held monopolistic positions before WWII are today world leaders. Previous Japanese oligarchic firms such as Mitsubishi, Sumitomo, and Mitsui, are now world renown and thriving well in competitive environments. Even Nippon Telephone and Telegraph (NTT), a former government-owned monopoly formed in 1952, is today a private corporation serving the needs communications needs of Japan, external markets, and enjoyed a 2017 revenue of $105B.

Oligarchies and Security Dangers to Small States