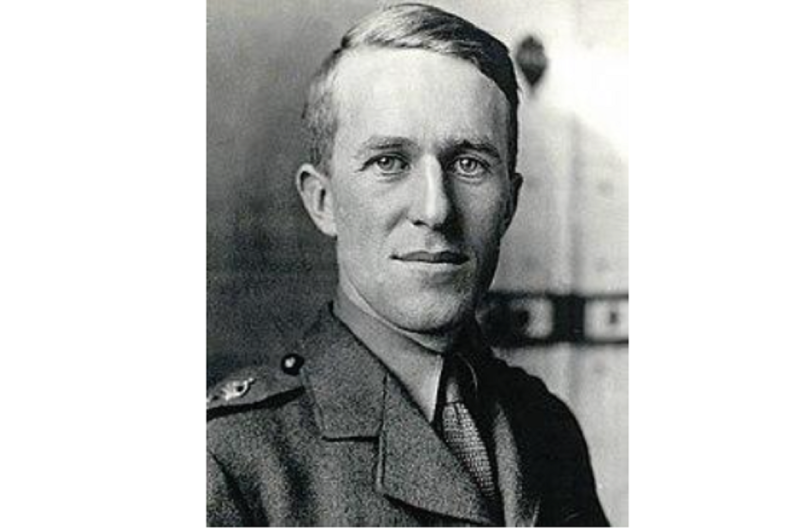

T.E. Lawrence (of Arabia), in a 1919 interview with Lincoln Steffens, replete with early twentieth century overtones, conveyed perhaps the prevailing political attitudes toward and by Armenians, respectively.

This interview has been used to vilify Lawrence as a racist and supporter of exterminating the Armenian people and other “old nations.” Among many things stated in this somewhat bizarre interview included,

“Killing and wiping this orphan race off the world seems to be the only solution,” and “The Armenians,” he said, “must not have Armenia, not the back lands. They would not work them themselves, not even for themselves. They would not even do the work of organizing the work or development. They would let them out as concessions to others to manage. They want to live on the coast, in cities, on rent, interest, dividends and the profits of trading in the shares and the actual money earned by capital and labor.”

It is suggested the entire interview be read to understand its varied contexts and not judge the rhetoric of the time by today’s standards, just as Shakespeare’s English would not pass a spelling checker. What may have been the basis for such an attitude towards Armenians? What characteristics have Armenians demonstrated? One must remember that during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the majority of the commerce through the eastern regions of Anatolia was in the hands of Armenians. About three-quarters of the population of Tsarist Russian Tiflis (Tbilisi of today’s Georgia) were Armenians, as were almost all its mayors. Armenian industrialists were competing with the Nobels and Rothschilds for Baku oil. Calouste Gulbenkian, aka “Mr. Five Percent,” was the first to exploit Iraqi oil and became one of the wealthiest people of the twentieth century. Reading between Lawrence’s lines, Armenians appear successful individually to the point of not wanting to do the dirty work it might take beyond enhancing individual success. Lawrence reiterates, “Armenians won’t work,” and any American mandate over Armenia (which was the main thread throughout the interview) would be treacherous because the Armenians would put themselves in a situation inviting extermination. Lawrence never explains further. Steffens summed up Lawrence’s thoughts as follows,

“We Americans are a commercial culture, as the Armenians, as all these old nations were that ought to be killed off.” He [Lawrence] nodded. “They thought they were developing business when they were really developing a certain variety of the human species—a race of businessmen dependent upon the productive labor of other people whom they do not now govern and who hate them because they can beat anybody at trade and live without working—liars, profiteers, parasites— the most practical brains with the most Christian ideals and manners.”

Lawrence didn’t dispute this summation, only suggesting he wouldn’t have been so candid.

Was TE Lawrence Prophetic?

For sure, Armenians are practical people, as are many others. However, Armenians are highly individualistic, as evidenced by how well Armenians succeed under the rule of others yet appear challenged under their own rule. Successful self-rule takes effort and requires some sacrifice toward a common goal. Unfortunately, there has been no utility demonstrated by serving a common destiny since the fall of the last Armenian kingdom in the fourteenth century. Perhaps this individualism, centered around the extended family, is the default status of the human condition. After twenty generations, overrun by Mongols and Turks, ruled by Persians, Ottomans, and Russians, surviving genocide and the forces of assimilation, Lawrence’s seemingly anecdotal observations, not his solutions, are not surprising.

The fall of the Soviet Union subjected the newly independent republics to targeted privatization leading to the creation of oligarchic structures. Each republic had similar emerging social yet divergent geopolitical issues. What was pilfering from the Soviet government turned into outright theft from one’s own country. While it can be argued that all countries have an undertow of corruption, some worse than others, with lobbying so complex making shell corporations appear transparent in comparison, some ex-Soviet states had mandates that should have been the priority over oligarch-creation.

One of those mandates was the national security of the newly sovereign Armenia. Armenia is not Luxembourg; rather, it is surrounded on seventy percent of its borders by aggressive neighbors. However, rather than address an existential threat from Turkey and a hydrocarbon-rich Azerbaijan, Armenia’s first ruling regime allowed the post-Soviet privatization process to create a new class of oligarchs, many from the Soviet period, that sold off the contents of national laboratories, factories, and agricultural facilities, without a thought of how they may enhance national security. Many in the oligarch class and cronies became (and some still are) members of parliament, monitoring the governing processes for their benefit. The result was an Armenian cult of oligarch envy with “success” not measured by the amount of effort and discipline that earned “success” but by cashing in on what was created by others for the enrichment of the individual. This system discouraged involvement by the Armenian diaspora, having waited for nearly three generations to help an independent Armenia. Armenia’s post-Soviet governments projected an unwritten ideology rejecting synergy with the Armenian diaspora. The Armenian diaspora could have served a unique role in building an Armenian state. If Armenian rulers had prioritized national security above all, rather than encouraging the default status of the human condition, Armenia would have created the institutions it lacks today, such as a strong military and especially a dynamic diplomatic corps that would have served Armenia’s interests and not those suggested by western institutions or functions as business liaisons. Armenia’s current government, having come to power on an anti-corruption platform, is supplanting a handful of hated oligarchs with an up-and-coming class of individuals waiting in the wings to sign contracts with Ankara and Baku, absorbing the so-called peace dividend from an ostensibly-engineered defeat in the 2020 Second Karabakh War.

Armenia should have understood Lawrence’s concept of an “old nation” as an emergent post-Soviet republic,” but it did not. Armenia is paying the price for this today. As a result of not maximizing one’s capabilities and not having a grand strategy that all national and extra-national institutions could use as a beacon — even the oligarchic class — Armenia is under an increased existential geopolitical threat resulting from events it didn’t anticipate or if it did, perhaps Lawrence was right after all.

Yerevan, Armenia

Author: David Davidian (Lecturer at the American University of Armenia. He has spent over a decade in technical intelligence analysis at major high technology firms. He resides in Yerevan, Armenia.)