David Davidian

April 2020

We need a philosophy of strategy that contains the seeds of its constant rejuvenation — a way to chart strategy in an unstable environment.

– Carl von Clausewitz

This study approaches topics definitionally. Many issues lack solid perspectives such as the concepts of national interest and grand strategies.

Armenia

The Republic of Armenia is not the culmination of a natural process of political and cultural evolution. This Southern Caucasus state is a progeny repository of the survivors of the Turkish genocide of the Armenians carried out under the guise of WWI. Only a few years after the end of WWI, what remained of landlocked Armenia was incorporated into the Soviet Union. Attempts at seeking justice for this genocide were forbidden by the Soviet authorities as such efforts would have been considered an expression of ethnic determination. Such attempts were a political affront to Soviet political philosophy, being entirely inconsistent with Marxist-Leninism. In addition, Vladimir Lenin capitulated to Turkish machinations ensuring the suppression of any Armenian political expression in exchange for friendly relations between Turkey and the Soviet Union. For genocide survivors outside of Armenia, mainly in lands south of Anatolia, in Europe, and the United States, it took two generations to rebuild their lives. These survivors were unable to counter the political influence of the Republic of Turkey.

While the active suppression of anything other than benign national expression was a hallmark of the Russian Soviet empire, the forced integration of constituent nationalities continued until the era of Glasnost and Perestroika in the latter half of the 1980s. At this time active, although in many cases unsophisticated, expressions of national determinism surfaced and manifested themselves differently across constituent Soviet republics and their ethnic minorities. In many instances, remnants of Russian KGB activity continued, influencing events in Soviet republics on the verge of declaring their independence as the Soviet Union was disintegrating. In many newly self-declared independent republics, breaking free from three generations of momentum created from Soviet central command was, and still is in most cases, challenging.

Today’s Armenia became geographically defined due in part to the 1917 Bolshevik revolution, which caused the withdraw of Russian troops from the Ottoman Turkish front lines during WWI. This retreat allowed Turkish forces to complete the extermination of the remaining Armenians and other non-Turkish people across the eastern regions of the Armenian Plateau. The invading Soviet Red Army of the early Bolshevik period prevented the complete Turkish destruction of what remained of Armenia and its people. The disillusion of the Transcaucasian Socialist Federative Soviet Republic in 1936 created the constituent Soviet Social Republics of Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia. The Armenian population of the region of Nakhichevan, having been placed under Azerbaijani jurisdiction years earlier, was pressured to emigrate. Azerbaijani jurisdiction over the Armenian-populated region of Nagorno-Karabakh remained. During the post-Khrushchev era, these Soviet republics engaged in actions in their local interests as long as not entirely outside of dictates from Moscow.

1965 was a turning point for Armenians, coming on the fiftieth anniversary of the genocide, eventually resulting in the construction of the Tsitsernakaberd genocide memorial. Expressions of crude ethnic identity continued until the disintegration of the Soviet Union in 1991.

Existential Threats

An existential threat, an expression that is almost cliché, is a force with the capability of permanently changing or coercing a target group’s behavior and communal activities, both of which are among the dominating actions against the latter’s will and interest. Assessing, categorizing and dismissing national threats is a dynamic process.

The Republic of Armenia is in a part of the world where state boundaries are drawn arbitrarily and are politically motivated, with many peoples denied statehood or autonomy. Such boundaries serve the interests of powerful states. Nevertheless, Armenia lies on the intersection of contentious regional and sub-regional powers, some of which engage in the influential expressions of national interests. Those entities include Turkey, Russia, Israel, Iran, and Azerbaijan.

Turkey

Turkey not only committed genocidal extermination of Anatolian Armenians under cover of WWI, but this genocide extended into areas outside of Turkish control into Persia, and Russian controlled Georgian and Armenian provinces. If conditions avail themselves, Turkish destruction of its Kurdish population and the remaining Armenians in the Southern Caucasus, including the Armenian state, is a distinct possibility. Turkish support for Azerbaijan in its demand that the Armenians of Nagorno-Karabakh surrender their sovereignty is quite clear. The threshold for direct Turkish intervention in the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict, in support of Azerbaijan, is a function of prevailing political costs to Turkey.

From its Ottoman incarnation to the present, Turkey is a state that is not only characterized by engaging in whatever it perceives is in its interest, but it has been rewarded for doing so. These “rewards” include: escaping judgment for the genocide of the Armenians; elimination of remaining Christian minorities within its recognized borders; and diplomatic gymnastics Turkey engaged in to induce mandate France to grant the Mediterranean Region of Alexandretta to Turkey in 1938. This “grant” was a quid pro quo not to side with Germany in any European conflict, to US Secretary of State Henry Kissinger support for Turkey to invade the Republic of Cyprus in 1973 and eventually occupy nearly 40% of its northern regions to this day. Today, Turkey took what was a US green light to invade northern Syria and eliminate Kurdish and other undesirable minorities along this border region. The apparent international tolerance of Turkey engaging in whatever it believes it can is a clear and present danger to what remains of Armenia when the right conditions exist for Turkey to express its irredentist goals.

The Turkish Advance into Northern Syria

On October 14, 2019, an overt pronouncement of the Turkish Misak-i Millî (Turkish National Oath) that has been a dream of Turkish foreign policy since the early 1920s, was made by the Turkish Defense Ministry. Whether as political hyperbole or an expression of the Turkish national ethos, it appeared on Facebook.1

Current Turkish Defense Minister’s Facebook Page with the Turkish Misak-i Millî Map

Center stage in the Turkish Misak-i Millî is a map that extends the borders of Turkey from Varna, Bulgaria to Salonika, Greece, much of the Aegean, Cyprus, from Latakia to Aleppo and across northern Syria, to Kerkuk, Iraq, Armenia, and the Georgian Black Sea region of Adjaria. Currently, Turkish forces filled the vacuum formed when US forces pulled out of northern Syria in the fall of 2019. Turkish troops are based just north of Aleppo across much of northern Syria and have bases across north Iraqi Kurdistan. Half of Cyprus has been occupied by Turkish forces since 1974.

Turkish military support for selected groups vying for power in Libya, attempted expansion of Turkish influence over Mediterranean gas deposits, and claims of an ethnic Turkish population in Libya, is part of a continual neo-Ottoman Turkish foreign policy. One need only read the recent tweet by Turkish President Erdogan2 to appreciate Turkish neo-Ottoman sentiments.

2016 Turkish Military Plans Against Armenia.

Documents obtained by the Nordic Monitor describes a Turkish plan presented to the General Staff by the Directorate of Operations that included air strike operations against Armenia called OĞUZTVRK Hava Harekât Planı (OĞUZTURK Air Operation Plan).3 The existence of these documents is very significant; moreover, it is unclear if this plan is part of a more extensive operation.

On October 6 and 7th of 2015, Turkish military helicopters twice violated Armenia’s airspace over Armenia’s Armavir province bordering the Igdir and Kars provinces in northeastern Turkey. Turkey claimed poor weather for the violation, which occurred days after Russian warplanes were accused of violating Turkey’s airspace while carrying out bombing raids in Syria. A request for explanation from NATO remains unanswered.

Turkish Inroads into Georgian Adjaria

The Georgian Autonomous Region of Adjaria and its Black Sea port and city of Batumi are under infrastructural influence by Turkey. This trend began in the immediate post-Soviet period but intensified with the policies of former Georgian president Saakashvili. This region could eventually be claimed as Turkish territory as per the tenets of the Turkish Misak-i Millî. Under the right conditions the Region of Adjaria could suffer the same fate as the pre-WWII Syrian Mediterranean region of Alexandretta.

Georgian overtures to Turkey are a strategic threat to Armenia. The Turkish blockade of Armenia’s western border could be extended north to these Black Sea ports where Armenia has vital trade interests. There is a spectrum of threats. Turkey could find itself in a position with Russia to squeeze Georgia economically with enhanced Turkish control over Adjaria in parallel with Russian pressure on rump Georgia. Since Turkey already has its border with Armenia blockaded, influencing or stopping imports to Armenia from Batumi and other smaller Georgian ports is a direct threat to Armenia. Armenia could be in an unacceptable situation with no access to Black Sea ports. Without a formal Turkish annexation of Adjaria, Turkish control over Adjarian Black Seaport traffic could be enough to threaten Armenia’s already fragile international exchange. This situation would place a heavy burden on the only other northern route through Georgia’s Upper Lars Highway into Russia. Since 1993, about seventy percent of Armenia’s borders have been under joint economic blockade by Turkey and Azerbaijan. Turkey both supports Azerbaijan and exerts pressure on Armenia to drop its campaign for genocide recognition by the international community.

Azerbaijan

In 1994 Azerbaijan agreed to a military ceasefire with Armenia and Nagorno-Karabakh over control of the region of Nagorno-Karabakh. This region has been majority Armenian populated for thousands of years, yet it (and the region of Nakhichevan) was placed under Azerbaijani jurisdiction by Joseph Slain in 1921 for various reasons, none of which were in the interest of its indigenous Armenian populations. The Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Region was created in 1923. The periodic petitioning of Moscow for Nagorno-Karabakh to be placed under Armenian jurisdiction was never successful. Subsequently, as the Central Soviet rule disintegrated, the battle for control of Nagorno-Karabakh ignited as early as 1987. Azerbaijanis lost control of this region in favor of the indigenous Armenians. Since 1994, Armenians have exercised sovereignty over this land while Azerbaijan claims this region as theirs.

Azerbaijan and Armenia have engaged in a military weapons arms race fueled by both sides purchasing armament from Russia. In addition, Azerbaijan has purchased billions of dollars of high technology weapons from Israel while providing Israel with half its crude requirements.

While Azerbaijan represents an existential threat to Armenian, Armenia reciprocates at least an equivalent threat to Azerbaijan.

Russian Commitment

Political and military commitments in the form of alliances can result in dilemmas. When states enter into partnerships or international associations, compelled into acting in the interest of the whole, it restricts that state’s freedom of action. A primary-class member of an alliance, such as a superpower, generally has more significant group influence than a subordinate-class member of an otherwise equal status military alliance. However, without clear responsibilities, member states in alliances may choose not to act for the common good, but rather serve local interests. The effectiveness of any military alliance is only as good as the quality and commitments of its members. After the Soviet Union disintegrated, definitions and purpose of existing alliances, such as NATO and the Warsaw Pact, changed drastically. The latter being fully dissolved. Each of the newly independent states of the former Soviet Union developed their own foreign policy directions, some more distinct than others. Other than Caspian basin oil, the West seemed to have little interest in the newly independent Southern Caucasus states. Russia considered the Caucasus part of its sphere of influence, thus Russian bases in Armenia were not abandoned. This partnership firmed up the Russian-Armenian military relationship. No other option for Armenia existed. Eventually, by 1994 Armenia became a member of the Kremlin-sponsored Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO), a military alliance with roots in the 1992 Commonwealth of Independent States Collective Security Treaty.

While the charter of the CSTO is public, any secret agreements, such as between Russia and Armenia are not public, handicapping any analysis. However, there are clear dangers in hedging a state’s long-term strategic interests on a single ally. One can only speculate on CSTO member action during a real conflict. The response of CSTO member states during the April 2016 Nagorno-Karabakh “Four Day War” between Armenian defense forces and the Azerbaijani Army brought to the surface CSTO member commitments clashing with local interests. These competing interests are caused by military and local policy dissonance. Not only does Russia sell arms to both Armenia and Azerbaijan (a non-CSTO member), other CSTO members states sell weapons to Azerbaijan as well. During April of 2016, CSTO member state, Kazakhstan, released a statement of neutrality in this military flareup. Another member Belarus, declared that the conflict should be resolved based on international legal principles of territorial integrity. The Belarus position is that of Azerbaijan. Russia didn’t appear to take a stand either way. One may reasonably question what the reaction of the CSTO would be if Armenia is militarily threatened otherwise?

With Russian soldiers currently supplementing Armenian-Turkish border security, one might assume, at least currently, Armenia’s security is in Russia’s interest. Russian interest in the Southern Caucasus today, other than keeping Georgia outside of EU and NATO integration, is to enhance pro-Russian policies across all three Southern Caucasus states. Russia has expanded its military bases in Armenia and controls strategic elements of Armenia’s infrastructure. However, state interests are fleeting and follow higher returns on alternative diplomatic engagements. With Russia and other states vying for influence in the Southern Caucasus, Russia can at any time unilaterally degrade Armenia from its sphere of influence in exchange for higher returns elsewhere. This condition is an existential threat to Armenia.

General Military Threats

Military threats on any existing state can be categorized into classes.

Internal insurrection These types of threats are generally in the form of ethnic or religious insurgencies. Demographically, Armenia is largely mono-ethnic with no tribes or clans. This characteristic is due to many reasons, but mainly, it was not the most desirable place to remain economically as the Soviet Union disintegrated. As non-Armenians emigrated from Armenia, the remaining demographics resulted in ethnic Armenians comprising 98% of the population. This puts Armenia in the same condition as states such as Japan. Many developing states work for decades or more to achieve the homogeneous demographic status of Armenia. The condition of Armenia with ethnic and social homogeneity is a strong strategic asset.

Conventional attack Given the right conditions, such as a Russian strategic retreat from the Caucasus, for whatever reason, given its current and projected military capability, Armenia could be overwhelmed by a unilateral conventional weapons attack from Turkey or in concert with Azerbaijan.

If Armenian strategic armaments are allowed to function as advertised by their manufacturers and not compromised by backdoor kill switches, these weapons combined with conventional attacks on Azerbaijan’s hydrocarbon infrastructure, including the main Baku-Tbilisi-Cehan pipeline, will set back Azerbaijan by decades and seriously disrupt hydrocarbon transport from Turkey to Europe. It is unknown if this is deterrence enough to moderate Turkish designs on Armenia.

Levels of unconventional attack This category includes cyber attacks, dirty radioactive bombs, biological weapons, contaminating water supplies, and other methods of asymmetric warfare. If an enemy goal is land acquisition and emptying Armenia of its population by overwhelming force, poisoning water supplies or subjecting Armenia to biological weapons a strong Armenian deterrent could be to detonate Armenia’s operating nuclear power plant and spent fuel storage, contaminating the land for decades or centuries.

Tactical and strategic nuclear attack Given the limited number of states with the capability of delivering nuclear weapons on Armenia, such an attack would be part of a more massive catastrophic war. There would be no military reason to subject Armenia to a nuclear attack. However, a tactical nuclear weapons threat on Armenia is a real possibility, if acquired by Turkey or, to a lesser extent, Azerbaijan.

Sovereignty and Interests

The first principle of the Order of Nation-States3 “is one that grants political independence to nations that are cohesive and strong enough to secure it’.”

The second principle is “a free state permits a nation to pursue its interests and aspirations according to its own understanding.”

Third, “the government of each state has the right and obligation to maintain and wield the only organized coercive power within its territory.” “The ability of the nation to maintain and cultivate its own unique constitution and traditions is the heart of national freedom, and it is this which becomes possible under the order of national states.” “…Each nation is in perpetual peril of losing its freedom to another or combination of nations.”… The non-transference of the powers of government to universal institutions … without the order of national states collapsing into an imperial order.”

The role of the state is to protect its citizens. Conversely, a stateless person has nearly zero recourse on the international stage. The above three principles demonstrate sovereignty resides on a spectrum. A superior ability of a state to uphold these three principles results in a higher degree of sovereignty and freedom of action. Anarchy prevails internationally; thus, states must keep maximum vigilance using all the instruments of power available to maximize sovereignty.

Some states may decide to keep their heads down, pursuing a subordinate foreign policy. While this may be a temporary tactic, it must not be a strategy. A head-in-the-sand tactic is an unsustainable position in a dynamically changing international environment.

The concept of the Order of Nation-States grants political independence to nations that are cohesive and strong enough to secure it. A state’s freedom of action is limited by its power. Power being defined in its broadest sense. National independence is in constant uncertainty as this order is neither established nor free from continuous threat. Many states or group of states maintain their definitions through balances of power, be they economic or military. The state is the only unit in international relations that has real political significance.

Interests are “a highly generalized concept of elements that constitute a state’s compelling needs, including self-preservation, independence, national integrity, military security, and economic well-being.”5

National interests exist in a dynamic hierarchy and are defined as vital, extremely important, less important, and secondary.6

Elements in this dynamic hierarchy should be continuously evaluated, updated, re-categorized, and re-classified. This hierarchy of interests is universal and apply to any state. It is assumed the processes described in this study have been repeated by the appropriate bodies within Armenia’s government, although nothing official publicly exists to the knowledge of this author.

Vital Interests are those important enough to fight over, characterized as non-negotiable, uncompromising in serving the basis for national survival and security.

Extremely Important Interests are those involving political and territorial sovereignty, perhaps bordering on non-military engagement. Note how items in this category can move to “vital” depending on intensity and context.

Important Interests are those such as economic stability and searching for better engagements and deals, avoiding those which would result in negative consequences for the state.

Secondary Interests include issues associated with well being, social stability, and other advantageous consequences. Secondary does not infer unimportant.

Some of these interests are clear, others vague, yet others are perceptions within a spectrum consisting of generalized abstractions. Many of these items are rooted in the real or socialized ethos of the state. There is no magic formula for determining in which interest hierarchy a particular issue resides. Nor is there a rule on cost/benefit associated with the defense of a specific issue. Without adequate background knowledge and intelligence, it is nearly impossible to construct and classify each interest in its class with accuracy. Even with adequate information, this job is difficult.

State Security

In specifying6 a state security item, removing as much ambiguity as possible, the following questions need to be answered. While some of these questions, and others like them, might seem obvious for constructing and analyzing state security, the confluence of their answers can generate many conflicting conclusions. The best answers available to the following seven questions may not result in a reasonable state security blueprint, as some element is always compromised for the sake of another.

Security for whom? While this might sound like an obvious question, its answer is not simple. One could respond with “the state” or “the citizenry,” but these responses are ambiguous. For example, if the state is run by oligarchs, does the army become relegated to private security force for the ruling class? Further, in the modern era, some military structures tend to support the concept of permanent wars, filling the coffers of their military-industrial complexes. Conversely, when weak states in a subordinate military status, serving the commitments of a military alliance, are forced to send troops and material to a battle that may have little to do with that state, whose security is that small state’s military supporting?

Security for which values? A state is comprised of many citizens. Those states with a socially harmonious demographic have similar enough values where they are easily definable. Countries in regions of perpetual conflict may value physical safety or strong defense as characteristics of national values. First world states may exhibit values closer to market dominance and strong economic relations with large trading partners. Threatened states may hold physical independence or at least certain degrees of autonomy as society-wide values. Certain states may proclaim “our way of life is threatened” without specifying the extent of actions necessary to secure counter this treat, whether real or perceived. Values noted here are not vital in the absolute sense. Preventing external energy source disruption, blocking the availability of clean drinking water, or preventing a maritime blockade, are not values, but vital interests.

How much security? Security is a relative term. Is a state more secure with two hundred nuclear weapons rather than two? Can a state be considered secure if it can defeat its enemies in two weeks rather than two months? Does the threat of retaliatory annihilation define adequate security? The qualitative value of vital interests can help define levels of security. The quest for “absolute security,” led to the creation of the Nazi Gestapo, and 1930s Stalinist USSR. In contrast, states such as Israel and many western European countries have strict security in place for the immediate time frame and employ state monopolies for the longer term.

From what threats? A wide range of definitions exists for the term threat. Today’s national threat may become tomorrow’s simple nuisance or vice versa. While specific threats may vary over time, it is imperative they remain subject to constant evaluation and substantiation. Without a complete understanding of each threat, ranging from global warming, clean drinking water, to regional antagonism and nuclear annihilation, their confrontation or methods of mitigation will most likely fail.

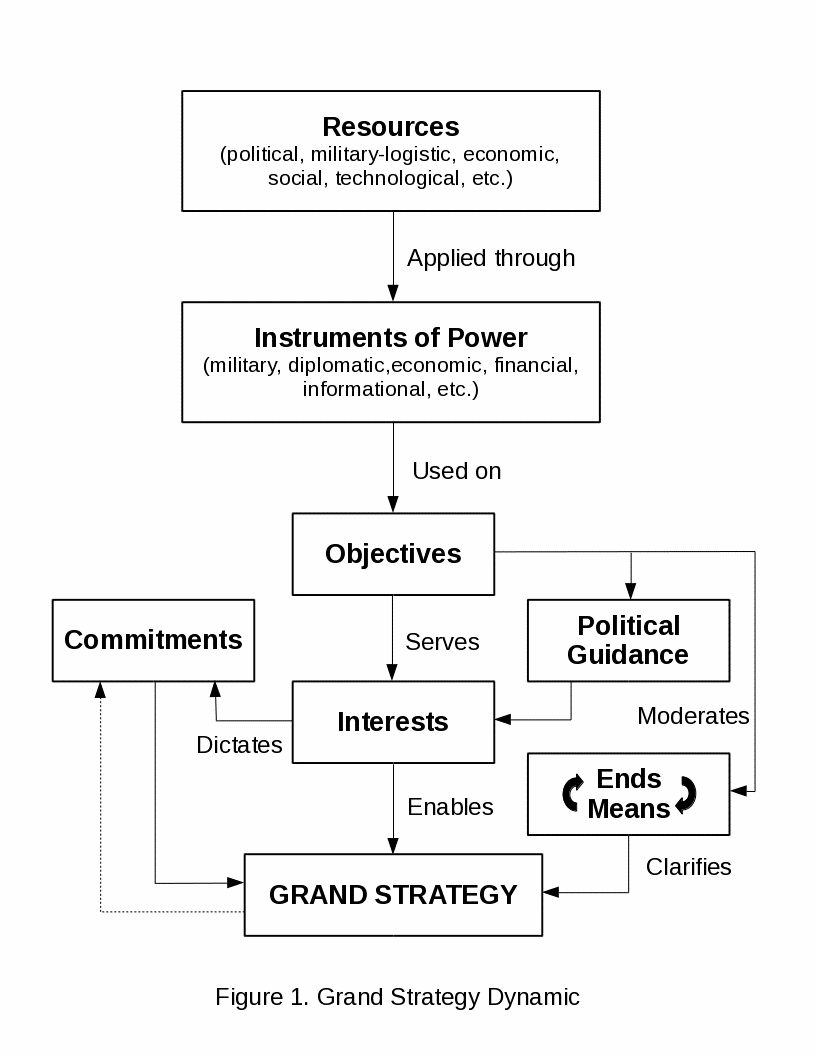

By what means? The logical follow-on to the previous question is to ascertain by what means can or must a threat be alleviated, moderated, or tolerated. The magnitude and potential immediacy of specific threats need to be correlated with the state’s ability to preempt or confront the specific threat. This action corresponds to ends and means, as seen in Figure 1.

At what cost? The cost of security at a minimum includes funding, political reaction, societal repercussions, logistics, potential losses from military actions, etc. There is also a cost for not engaging in specific activities. A realistic evaluation of the relative cost and benefits will determine the breath actions possible.

During what period? All previous six questions are dynamically interrelated, but all have the time function of immediate, short term, medium-term, and the long-term period within which actions can proceed. Some developing countries feel as though it is unnecessary to project security issues beyond the medium-term. In contrast, developed countries project in time a couple of generations forward in their analysis of security issues and in preparing in the short and medium term for actions decades ahead. Short-term activities and moreover medium-term security efforts must support long-term goals. Preemptive actions in the short and medium-term should set the state for long-term goals. Much of this is part of the overall grand strategy.

There is no magic formula one can use to weigh and reduce the various conceptual questions and realities that comprise state security. Regardless, the quality of national sovereignty can be, in part, indexed off of rational analysis and actions resulting in establishing adequate security in the national interest serving the grand strategy.

Grand Strategy and Strategic Options

Grand strategy is the “art and science of employing national power under all circumstances to exert desired types and degrees of control over the opposition by applying force, the threat of force, indirect pressures, diplomacy, subterfuge, and other imaginative means to attain national security objectives.”8 Grand strategy is intimately related with national security.

A state’s grand strategy is inclusive of existing or potential threats. Thus, the accurate projection, understanding, and dynamic correction of internal societal, economic, regional, and international threats and assets are required to begin both the establishment of national security and the establishment of a grand strategy. In spite of having the best available data and state actor assessment, the risk is implicit in evaluating national strategy and associated grand strategy. In making projections errors can occur based on chance and inherent analytical imprecision. National interests lead to policies, and policies are patterns of actions for attaining specific objectives.

Strategic options assume strategy goals, and these goals are predicated on interrelating ends (national interest) and means (instruments of power). See Figure 1, and note that the delineation between categories is porous yet highly interrelated. Instruments of Power are used on Objectives, and the latter is the ends to achieve in furthering or maintaining the state’s interests. None of the estimates, predictions or forecasts associated with reasonable objectives based on resources and Instruments of Power, even constrained by acceptable risks, must not be left to guesses, chance, or assume others will serve your objectives. Just as in business or everyday life, a strategy is required to get from point A today, within a known context over time, to an unambiguous point B. Creating the necessary contextual environment to reach point B is predicated on applying the necessary resources.

Operationally, strategy formulation is a proactive, dynamic, anticipatory process. It is not reactive. Just as the metaphoric definition of diplomacy as “the art of the possible”, establishing realistic policies is based on the limitations of the instruments of national power. Strategy is not planning, but planning is based on strategy.

Within state structures, all successive planning and execution should be based as closely as possible on the grand strategy. In this way, all vectors of tactical actions taken by multiple tiers of state structures point in the same general direction, some with better means than others. When ends are well understood they can be achieved. It is planning that fills the separation between strategy and execution.

In On War, Carl von Clausewitz wrote, “Tactics are the use of armed forces in a particular battle, while strategy is the doctrine of the use of individual battles for the purposes of war.” Clausewitz tells us tactics are about the use of the instruments of power in successfully waging battles. Still, strategy tells us what battles to fight, why, and how they contribute to the overall purpose and goal.

Formulation of a Grand Strategy.

Carl von Clausewitz also wrote, “The talent of the strategist is to identify the decisive point and to concentrate everything on it, removing forces from secondary fronts and ignoring lesser objectives.” Clausewitz military prowess concluded that the best strategists require situational awareness, an understanding of the military and political context of the environment. The best intelligence allows the dynamic strategist to determine what instruments of power to concentrate, what not to utilize, and stay on the central objective, relegating “lesser objectives” as subordinate. Objectives being “the fundamental aims, goals, or purposes of a nation toward which policies are directed and energy are applied. These may be short-, mid-, or long-range in nature.”8

A state’s grand strategy should not be subservient to the politique de la jour of international structures. This failing will result in reduced sovereignty. However, the cost of limiting a state’s strategic options has to be weighed against reasonable international cooperation. Among the reasons why some states are not members or part of any military block is because they may find themselves having to sacrifice lives and engage in activities not in their best interest or serving their values. Other states find themselves in positions to offer their services to political/economic/military blocks in return for various degrees of protection, perceived or otherwise. Commitments have their feedback loop in the Grand Strategy Dynamic Figure 1 flowchart, outside of the direct Resources/Instruments of Power/Objectives/Interests//Grand Strategy vector.

The Figure 1 flowchart is an attempt to provide a visual representation of the general categories and prerequisite operations required to generate and maintain a Grand Strategy. As noted earlier, many of these categories overlap. The assumption made is that a state exists with Resources and Instruments of Power.

Going through the chart, Resources become actionable through a mechanism to project their power. Instruments of Power are devices fulfilling Objectives. These Objectives serve particular Interests, thus fulfilling the state’s Grand Strategy doctrine. One must go up and down the central flowchart vector, including Ends and Means, to achieve a convergence between Resources available and the overall strategy. Political Guidelines may dictate the establishment of additional Resources or mechanisms to project them through Instruments of Power, as a function of the state’s Interests.

Commitments may exist, but they are the result of Interests, that in turn, become part of the Grand Strategy, which also dictates the extent of these Commitments, usually in the form of military/political or economic alliances.

State institutions serve the grand strategy in their independent way.

Armenia’s Strategic Interests, Assets, and Options

In this introductory overview, describing items associated with Armenia’s interests, assets, and strategies will be attempted. As with all such efforts, without knowing the extent of state Resources and Instruments of Power, such exercises lack background information. However, each observation is more realistic than wishful thinking. Also, what is being presented may already be part of Armenia’s Grand Strategy, and readers should not assume anything either way. Many states have similar interests at the highest levels, and some have the ability to affect their objectives fully.

Vital Interest: Survival of Armenia

Objective: Deter Armenia from being militarily annihilated with either overwhelming conventional force, weapons of mass destruction such as nuclear, chemical, or biological weapons.

Strategies (sample, non-exhaustive)

- Identification of alliances of mutual military interest

- Expand any indigenous arms industry with all appropriate military preparedness

- Prepare the Armenian diaspora worldwide to participate in diplomatic, economic, and military responses

- The Republic Armenia’s ultimate response to an attempt at destroying Armenia and its people, by the Republic of Turkey, is to perform a controlled core breach of the Armenian Nuclear Power station (ANP) at Metsamor. In parallel with a full power core breach, the planned burning of ANP spent fuel storage facility would add to the radioactive contamination. Geographically, this act would be much worse than the radiation poisoning effect of conventional nuclear weapons. This last act of desperation would not only make much of eastern Turkey and Armenia uninhabitable for many decades but parts of Azerbaijan, Iran, Georgia as well. It is not known if such a plan exists in Armenia’s strategic military repertoire, but its acknowledgment in this document may have made it so. This full-power, full-breach option, however repulsive, will serve as the strongest deterrent against an active second genocide of the Armenian people and the land acquisition of what remains of Armenia, highly discouraging the destruction of Armenia and the extermination of its people. This policy is similar to Israel’s Samson Option.10

Extremely Important Interest: Armenia’s Independent Economic Survival

Situation: Armenia’s four main methods of international commerce is through Georgian Black Sea ports, the Upper Lars Georgian highway, the border town of Meghri at the Armenian-Iranian border, and air cargo. Armenia’s gas supply is mainly through a pipeline from Russia through Georgia. The remaining 10% is from Iran. This situation can quickly move to vital if any Georgian routes are compromised.

A sovereign Armenian land route to the Black Sea would facilitate transport to and from Iran, Iraq, and Iraqi Kurdistan (both through Iran), perhaps Syria (through Iraq), as well as provide an alternative route for Russian and EU products heading south. This route would enhance the Chinese Silk Road initiative, providing additional transport dynamics. A sovereign land route would be part of the Armenian state with central authority over this geographic area, its population, and defense.

Objective: Ensure Armenia will never be blockaded entirely, can feed itself, engage in commerce, and not have neighboring states deter its economic growth.

Strategies (sample, non-exhaustive)

- Be prepared to militarily secure transport routes through Georgia if negotiations fail between gas sources and those forces preventing its transport. The same for truck and train transportation.

- Prepare the groundwork for hydrocarbon transport and commerce through Iran, including alternative roads through the region of Nagorno-Karabakh.

- Secure a sovereign landmass from Armenia’s current western border to the Black Sea, which should be awarded to Armenia as genocide reparations. This would simultaneously release Armenia from its landlocked condition, removing the dependence on Georgia, Russia or Iran.

Map 1 Genocide Land Repatrations Creating a Soverign Landmass from Armenia to the Black Sea (www.regionalkinetics.com)

Strategic Assets

Strategic assets are needed by a state in order to achieve its objectives. Such assets may be rare and in some cases unique. Strategic assets might be an economic system, societal harmony and cohesion, decades or centuries of foreign policy and diplomatic experience, a space force, a crack intelligence agency, a well disciplined and educated population, etc. In contrast, a state’s tactical assets would include rockets, tanks, soldiers, warplane, etc. A few samples of Armenia’s strategic assess will be followed by suggested actions that would enhance Armenia’s sovereignty.

Strategic Asset: Worldwide Diaspora

The unique role of the Armenian diaspora is a strategic asset that must be fully harnessed, for its contribution is time-limited as the forces of assimilation take their toll. The active engagement of this diaspora in Armenia’s Grand Strategy as an Instrument of National Power is probably taking place, but must be expanded.

Due to the physical dispersion of Armenians after the Turkish genocide, Armenians are found in nearly every country with some politically and economically influential. All Armenians, either in Armenia proper or in the diaspora, view the security of Armenia as a paramount goal.

Strategic Asset: Mono-Ethnicity

Mono-ethnicity, in the form of social and cultural coherent homogeneity, has been a central goal of despots and dictators since time immemorial. In the early post-genocidal years followed by increased Soviet repression, Armenia was never a place of easy success. Its landlocked geography, combined with the special suppression of national expression during its Soviet-era, created enough centrifugal forces that filtered out non-ethnic Armenians from the population, leaving a vast Armenian majority. The mono-ethnic nature of Armenia is on the order of that of Japan or Lesotho in southern Africa. In the post-Soviet era, similar forces drained out even more of Armenia’s non-ethnic Armenian population. What many globalists may judge as antithetical, Armenia’s mono-ethnic nature has both eliminated the ability of stronger powers to catalyze minority insurrection and provides Armenia a level of societal cohesion unlike any of its neighbor states.

Expressions of Enhanced Sovereignty

Sovereignty is hardly absolute. The uncontested rule of authority over territory is a somewhat simplistic, anachronistic definition of sovereignty. Instead, sovereignty exists on a scale ranging from what is associated with a poorly run failed state, states ruled by oligarchs enriching themselves, superpowers who can project their influence on a global scale, to every gradation in between.

Sovereignty and its expression are constantly challenged in the anarchic international order. State security, levels of sovereignty, state defense and offense, are directly related. Just as many terms introduced in this study, solid definitions for these terms are illusive. Internal state sovereignty generally in democratic-leaning countries comes from citizens bestowing local control and power on security structures. Another dynamic exists at the international level.

The Order of Nations, the modern international collection of states, allows certain characteristics to be granted to or tolerated on states. Ironically, the fifteen constituent republics of the former Soviet Union were awarded the status of nation-states, qualified to join the United Nations, yet twenty-five million ethnic Kurds haven’t qualified for the same. The United Nations Charter Article 2, Item 1, affirms “The Organization is based on the principle of the sovereign equality of all its Members.”, yet provide little explanation for either sovereign or equality.

Some expressions of sovereignty are enhanced or moderated by alliances, while others are enacted unilaterally. The chances of the Armenian-administered region of Nagorno-Karabakh keeping its sub-state sovereignty, in the United Nations sense, without it being partly in Russian interest, would be currently very difficult. The [second Albanian] state of Kosovo, carved out of Serbia, recognized by some states internationally, is still not a member of the United Nations. Non-super power state actions such as the Israeli Operation Entebbe, the Israeli destruction of Iraq’s Osiris Nuclear facility, the recent French commando operation in Burkina Faso, are examples of actions that operationally enhance sovereignty, considering they result in enhancing state security by demonstrating there is a serious deterrence when a state or its citizens are threatened or even if there is a perception of threats.

For varied reasons, modern states claim self-sufficiency, self-reliance, and some even claim to be economically independent. By the end of the 20th century, such claims are not demonstrable since economic globalization has taken its course, even with parochial reactions in the form of major power protectionism, and populism manifest in initiatives such as Brexit and America First.

The maintenance of superpower sovereignty has its own coercive dynamic, as are those who lobby for superpower “assistance” in their sovereignty. Among those who claim to be incontestable military or economic powers engage in never-ending interference in each others internal and external spheres of political and economic influence, intimidate emerging states, and increase the complexity of co-existence.

During the United States presidency of Barak Obama, the United States extended its already overarching sovereignty by the “targeted killings” of five hundred forty two individuals. Classically, such killings are called state-sponsored assassinations. Superpower sovereignty has certain uncontested privileges unavailable to those of diminutive status.

Suggestions for the Incremental Enhancement of Armenian Sovereignty

Arguments can be made for and against engaging in the actions suggested below since all such activity should serve the grand strategy. However, without having a stated Armenian grand strategy as a reference, the following suggestions are at best interesting. Depending on the breadth of the grand strategy, these suggestions may be appropriate. Some of these suggestions are about events in the recent past, and others can also serve to enhance internal sovereignty. Some are categorized as expressions of soft power. These suggestions are not meant to be exhaustive or reckless but rather introduced for retrospection. As with all actions, their cost-benefit, ends-means, etc. need to be evaluated with respect to the grand strategy, moving from the top to the bottom, as shown in Figure 1. Specific social and economic suggestions are being omitted for the sake of brevity, avoiding a litany of further complexity, and instead, centers on selected political and military issues.

The state’s social and economic development is predicated on past, current, and future strategy, its expressions of sovereignty, and the political environment it has endeavored to achieve.

Sovereignty Enhancement: Armenian woman tortured and murdered in North-West Syria

Background: Islamic terrorists from the Jihadist organization Jabhat al-Nusra raped and stoned to death a sixty-year-old Armenian woman, Suzan Der Kirkour, found dead outside of the village of al-Yaqoubiyeh. in the Syrian province of Idlib.11

Actions taken: None

Suggested action: Engage in a covert military operation to track down and exact justice in parallel with a well architected public relations campaign.

Benefit: Armenia will be known as a state that defends its own, including diaspora Armenians. A successful operation will tend to deter future attacks like this in the international space.

Detriment: The operation could fail. Terror reprisals could occur in the same area. An inadequate or mismanaged public relations campaign could frustrate an otherwise successful operation.

Sovereignty Enhancement: Armenian Yezidi soldier beheaded

Background: Kyaram Sloyan11 was an Armenian Yezidi soldier killed during the April 2016 Armenian–Azerbaijani clashes in Nagorno-Karabakh. After his death he was beheaded.13 Videos and pictures showing Azerbaijani soldiers posing with his severed head posted on social networks.14 His head was taken from village to village like a trophy.

Actions taken: None

Suggested action: Engage in a covert military operation to track down and exact justice in parallel with a well architected public relations campaign.

Benefit: Armenia will be known as a state that defends its own and can execute justice even in enemy territory.

Detriment: The operation could fail

Sovereignty Enhancement: Old Nakhichevan Cemetery Destruction

Background: The Armenian Cemetery in Julfa was situated near the town of Julfa in the Nakhichevan exclave of Azerbaijan. The site contained on the order of 10,000 tombstones and monuments consisted mainly of medieval Armenian stones crosses. Azerbaijan began the destruction of this cemetery in the late 1990s. By 2010 Azerbaijan finished the destruction and the site was turned into a military target range. This was the largest collection of medieval cross-stones in existence.

Actions taken: Official appeals were filed by Armenian and international organizations, condemning the Azerbaijani government for such targeted cultural destruction. Many other groups and individuals demanded Azerbaijan desist from such activity.

Suggested action: Engage in a covert military operation to track down and bring those responsible for this massive destruction to justice in parallel with a well architected public relations campaign.

Benefit: To let it be known that Armenia can effect actions with an international following outside its borders, in enemy territory, when events have taken place to the determent of the international community and Armenian interests.

Detriment: The operation may never be brought to completion. As time moved on, the ability to determine those responsible is greatly diminished.

Sovereignty Enhancement: Hidden Armenians

Background: Many people in eastern Turkey are known as hidden or Crypto-Armenians. These people are what remain of the forced Islamization of Armenians during and after the Turkish genocide of the Armenians. Many know of their Armenian origins, yet due to conditions in Turkey, these people stay hidden, slowing assimilating into a Turkish mainstream. Included in such forced hidden peoples are Crypto-Greeks and Georgians.

There is an older, yet significant group of assimilating Armenians known as the Hamshen people. The Hamshen people span the geography from an Islamized concentration in far northeast Turkey to nominally Christians in Abkhazia and the Krasnodar region of Russia. Some Hamshen speak their own dialect of Armenian, others speak local languages.

Actions taken: Over the generations, many of these hidden Armenians have slowly migrated to Istanbul and some have re-integrated into what remains of Armenian life in Turkey’s largest city. Armenian media broadcasts have traditionally catered to these peoples.

Suggested action: Expanded soft-power cultural re-enablement of all such peoples.

Benefit: As part genocide reparations, a landmass providing a continuous land connection between Armenia and what is currently far northeast Turkey will necessitate the re-integration of these peoples on this reparated land, if choosing to do so, into Armenian society.

Detriment: Any over-exposition of hidden Armenians in Turkey given in the repressive ethnocentric environment in Turkey will generate harsh reactions against them and will further isolate what remains of these Armenians. This initiative must be executed in parallel with demands for hard genocide reparations.

Sovereignty Enhancement: Hard Genocide Reparations

Background: Armenians were subject to systematic genocidal extermination by the Turkish government. This extermination was the central initiative in the Turkification of Anatolia’s peoples. A million and a half Armenians were murdered, their land and property stolen. Damages against Turkey and supporting powers are on the order of three trillion dollars.15

Actions taken: Efforts toward genocide recognition began in 1965, and as of this writing, over thirty countries have recognized this genocide as a historical fact, but none have supported reparations.

Suggested action: As part of an Armenian grand strategy, policy initiatives need be commenced demonstrating how this particular genocide reparations is in the interest major world powers and neighboring countries. Plans, simulations and scenarios need to be expanded beyond the current efforts.

Benefit: Genocide reparations, even minimally as part of Armenia to the Black Sea land reparations (see Map 1), will ensure Armenian economic survival, significantly reducing or eliminating constant threats by neighbors, and allowing the international coercion against Armenia to be minimal.

Detriment: None

Sovereignty Enhancement: Engage in State of the Art Political Public Relations

Background: Due to big-power politics and regional rivalries, a politically diminutive Armenia has been used and portrayed in a negative light. The hyperbole Armenia has been subject to is sometimes random, but at other times organized in theme and goal.

Actions taken: No activity appears organized by either the Armenian government or those having the ability to counter such anti-Armenian activity or sustain a pro-Armenian presence on social media.

Suggested action: Enlisting the most qualified individuals to engage in media-based targeted advocacy and public relations activity using lessons learned from other successful international programs.

Benefit: Counter and deter anti-Armenian social media activity and engage in programs that positively influence perceptions within local and international political, economic, and social structures. Armenians need to establish the agenda.

Detriment: None, unless expanded efforts are incompetent.

Sovereignty Enhancement: Encourage Dual Citizens to Reside Permanently in Armenia and Nagorno-Karabakh

Background: Dual citizenship is recognized between Armenia and many countries, such as the United States. During times of political tension, the existence of citizens from major states would tend to moderate external aggression and other actions.

Actions taken: Armenia actively encourages the repatriation of Armenian from its diaspora.

Suggested action: Engage in targeted programs that will attract both young and retired Armenians, particularly from first world countries, Russia, etc., to permanently reside in Armenia or Nagorno-Karabakh. The goal is to have a critical number of citizens from major states, increasing the ability of Armenia to enhance external protection of these citizens.

Benefit: Increases the security of Armenia, the contribution of diaspora Armenians, both from the vibrant young and well-trained to retirees who can contribute their experience and spend their later years in Armenia.

Detriment: None, unless expanded efforts are incompetent.

Sovereignty Enhancement: Enable Heavy Investment and Settlement in Nagorno-Karabakh

Background: In 1994, after almost a century of attempting to reduce the Armenian presence in the region of Nagorno-Karabakh by the British, Turks, Russians, and finally the Azerbaijanis, the indigenous Armenian population fought Azerbaijan and won sovereignty over this land. Since that time, Armenia, representing itself and the interest of Nagorno-Karabakh, and Azerbaijan have engaged in fruitless negotiations. Investments are a priority for the administration of Nagorno-Karabakh.

Actions taken: Currently, there is medium-level investment in Nagorno-Karabakh, but limited for many reasons.

Suggested action: Engage in a massive push for external investments by both the Armenian diaspora, the Armenian government, and interested third parties. Specific endeavors should serve the enhancement of sovereignty and include “feet-on-the-ground”. Further suggestions are outside of the scope of this paper.

Benefit: Not only will the internal sovereignty of Nagorno-Karabakh be served, with an increase in GDP and medium income, but Nagorno-Karabakh will start approaching the point of being recognized as an entity as its international sovereignty will approach that of recognizing states. Both Turkey and Azerbaijan would find this objectionable, as this will also increase Armenia’s sovereignty.

Detriment: None, however As Nagorno-Karabakh increases its sovereignty, Russia will have to adjust its policy in kind.

David Davidian is a lecturer at the American University of Armenia. He has spent over a decade in technical intelligence analysis at major high technology firms. The views expressed are not necessarily those of the American University of Armenia, the governments of the Republics of Armenia, or Nagorno-Karabakh.

References

1 https://www.facebook.com/HulusiAkarr/

2 @ObservatoryLY #ERDOGAN: “#Turkey cannot be confined within the 780,000 km2 border. #Misrata, #Aleppo, #Homs & #Hasaka are outside our actual borders, but they are within our emotional & physical limits, we will confront those who limit our history to only 90yrs.”

3 https://www.nordicmonitor.com/2019/11/turkish-military-planned-military-action-against-armenia/

4 The Virtue of Nationalism, Yoram Hazony, Basic Books, NY, 2018, Chapter XVIII

5 Grand Strategy, Principles and Practices, John M Collins, US Naval Institute, 1973, page 273

6 The Commission on America’s National Interests, Graham Allison, et al. https://www.belfercenter.org/sites/default/files/files/publication/amernatinter.pdf

7 The Concept of Security, Review of International Studies, David A. Baldwin, 23, 5-26, 1997, British International Studies Association, pages 13-17

8 Op Cit, Grand Strategy, page 269

9 Op Cit, Grand Strategy, page 273

10 The Samson Option, Seymour Hersh, Farber and Farber, 1993

11 https://www.jpost.com/Middle-East/Jihadists-stone-Christian-woman-to-death-in-Syria-595978 http://www.syriahr.com/en/?p=134949

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Murder_of_Suzan_Der_Kirkour

12 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kyaram_Sloyan

14 http://asbarez.com/149796/aliyev-awards-officer-who-decapitated-artsakh-soldier/

15 Armenian Genocide Losses http://armeniangenocidelosses.am

Further Reading

Schools, Mosques and Restaurants: Understanding Turkey’s “Soft Power” in Ajara, Sona Sukiasyan, Yerevan State University, 2017, https://cccsysu.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/Sukyasyan-S.pdf